|

A white man’s response to Black Lives Matter Racism: This is how it starts: This is how it ends!

When you feel small, there’s not much to make you feel bigger unless you can find someone else you can make smaller. There never seemed to be much recognition of the class driven roots of our predicament. Mostly it all just turned in on itself; community eating community with slow digestion and the crap only occasionally made visible when the boozer emptied or one gang of lads strayed over the invisible borders between gable end and crossroads, or the heavy bellied girls destined at 15 to be pushing prams to the corner shop instead of pens in school.

I remember no racism because there was nobody to be racist about, at least not in person. We were all white for miles and miles around. At least the miles we knew, in a place where nobody travelled then much anyway. It was there all right, the othering of others, but in early childhood it was way beyond my radar.

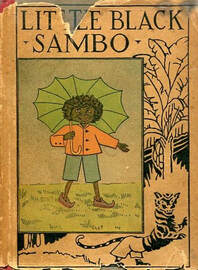

But his colour, I was fascinated, awed by it... I had never seen such a thing, not in another living human being. Hitherto just the golliwog or a schoolbook Little Black Sambo. Then we just got on with it and played like kids do. I remember noticing difference, yet still we just messed about, in the street, the house, the backyard. Eventually we played spin-the-bottle like kids do when some inkling of sexual difference is arising. But really, this time, we, the white ones, wanted to see if he, the brown boy, was the same colour all over. I remember his name now, unusual it sounds now as it did then. Streddik. I have no idea if I’ve got the spelling right. His sister’s name eludes me. Their surname is gone too, though as I write there’s a sound keeps humming “Johnson”—maybe it was that simple.

ways with Streddik, either you wanted to be his friend because he was different, interesting and exotic, or you wanted him squashed for the same reasons. He spent the days in the playground either with a friendly arm around his shoulder or someone’s fist in his face. Then he was gone as swiftly and unremarked as he arrived. I’d found out he was brown all over by the way, just as he found out that we where white all over. It was just curiosity, difference noticed without judgement, neither better nor worse than the other. Just different. And the difference ignored once explored and past interest. Yet I noticed something else at that time. Half-heard words from those greatly taller than me who seemed to move in another world so high up.

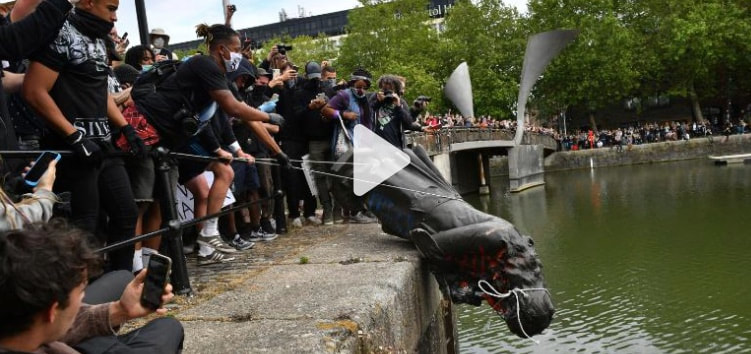

Leap forward to grammar school, where I was put in Clive House, because in faux public-school style we boys were allocated “houses” to encourage team spirit and identity... all names of English men who helped make all those red places on the map—Drake, Hudson, Raleigh, Clive. Eighteenth century Clive attended the same school as me; a plaque, proudly displayed, affirmed the honour we had in following him, he the spirited adventurer who set out to make his fortune in India and add to the foundations of empire—a role model for us all. Nobody told us those fortunes and foundations were built on the ripped-off wealth of India and the bodies of dead Indians. The school and the plaque are all gone now, under a bijou housing estate. If it were not so, would there be a demo’ today breaking into that sacred school hall to rip that testament down and cast it into the Irwell?

When I came back to the UK the pressure was on to get a job. I ended up in nursing school. There were fierce lessons to be learned and the least of them was how to care for patients. The hospital culture was unlike anything I had ever known, that’d be worthy of a book someday. But when it came to colour differences, it was as if the Universe had decided to teach me a few lessons of her own. Here we are, in that first month in school, February 1971; myself in the middle at the back with Christine before me, and Neville to my right. The three white Englanders; Mrs. Walker our teacher stands smiling on the right of the picture at the back, Mohammed next to her and Laxmi from Mauritius top left... (oh how the whole hospital had to give them English names ‘Colin’ and ‘George’ because their own were seen as too difficult to pronounce). Then there was Annie from Hong Kong, sitting on the extreme right, then Brenda from Sierra Leone, Jacquie from Jamaica extreme left and Alberta from Ghana next to her. The Empire had struck back and sent all her children to the motherland. Now will you wake up?

Of course, lot’s of people don’t want to know, or keep their heads in the sand... there isn’t really a problem anyway. We don’t know because we chose not to inquire. At the end of the film Downfall, Hitler’s secretary, Traudl Junge, is interviewed about life in Germany at the time, and her ignorance, and that of many Germans, of what prejudice was being acted out in the form of annihilation of the “others” in their name. She said, “We didn’t know about it – but we could have asked.” Maybe more of us palefaces can ask what it’s really like to be black in a white world. Maybe, too, looking at that brokenness in whiteness is one of the ways, in these times of world-wide protest, gathered around the death- dealing kneeling on George Floyd, that those of us who carry these old wounds and prejudices can speak authentically, confess of them. We can give up trying to bury this evil behind chronic niceness to people of colour, or express certain PC views aloud because we know we “should”. In the encounter with ourselves is the possibility of transformation, no, transmutation, turning lead into gold. Black people only have racist problems because white people have racist problems. “In the encounter with ourselves is the possibility of transformation, no, transmutation, turning lead into gold. Black people only have racist problems because white people have racist problems.”

of our own enslavement. The chains that bound us to fear and otherness, hidden deep and sometimes not so deep in the psyche, crying out to be made free, whole and integrated. Just like the wider world we live in really. The statue of Colston, slave trader, was brought down in Bristol. A jury decided in 2022 the perpetrators were not criminals for doing so. There are other monuments to be demolished, invisible, in our own hearts. Harder to expunge than anything cast in bronze, racism is sculpted by fear in each of us. Like Colston’s memorial figure, it took individual and collective action to recognise its presence and its power — and be rid of it. © Stephen Wright January 2022 About the Author

success of it, eventually becoming the first consultant nurse in the NHS in 1986. He got into conference speaking and course-leading internationally, shuffled around in academia, made TV programmes, wrote lots of books and research papers about nursing, advised governments and WHO and the Royal College of Nursing, and matured his craft in the nursing practice of older people culminating in leading a radical nursing development unit that influenced nursing far and wide. He gathered lots of glittering prizes along the way to add letters before and after his name, which appealed greatly to the Enneatype 3 personality he carries around with him. Thus all the usual trappings of an acclaimed career were in place. A hand-break turn in self-perception and a reawakening of the mysticism long suppressed since childhood took him in a different direction in the 90’s — exploring spirituality as it related to himself, health care and as service to others. He trained with some eminent teachers and was mentored most deeply by Ram Dass and Jean Sayre-Adams. He is a member of the Iona Community and his latest work with Wild Goose focuses on the life of Kentigern/Mungo and offers a pilgrimage route around the Northern Fells of Cumbria. Other books have explored spirituality and health, pilgrimage, poetry and the quartet of spiritual guidance, Coming Home, Contemplation, Burnout and, latterly, Heartfullness. The last of these is the culmination of decades of work and the teachings offered in the Kentigern School for Contemplatives, supported by the local diocese. Like many others, he hangs on by the fingernails to participation in the Anglican Church, but it’s where he fits and feels called after a life of nomadism, and where he finds service. He’s a Fellow and visiting prof’ at the University of Cumbria which offers some degree of input still to the academic world as well as conferring some vague respectability to his work. He lives with his partner in the English Lake District, enjoys grandfatherhood and his organic garden and at 72 still finds working as a trustee and spiritual director for the Sacred Space Foundation a joy. Here's our link to learn more about the Sacred Space Foundation's story >>> Image Sources:

Black & White Hand: https://unsplash.com/photos/7j3nCPOQbDQ • 1950s Children: https://www.standard.co.uk/lifestyle/london-life/photos-of-1950s-london-a3768851.html • Black girl with pigtails: https://unsplash.com/photos/lt-JRmS3VrU • Black Boy: https://www.pexels.com/photo/grayscale-photo-of-boy-sitting-on-stair-1328404/?utm_content=attributionCopyText&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=pexels • Little Black Sambo Cover: https://www.abaa.org/book/136214653 • Black Child's Face: https://pixabay.com/photos/child-face-african-africa-poverty-4617142/ • Hooded Head Down: https://unsplash.com/photos/Ew33MrOqVp0 • School of Nursing: From the author's archives • Jump for Joy: https://unsplash.com/photos/ZKdtR_3gVw4 • Saying Sorry: https://www.pexels.com/photo/upset-woman-listening-to-friend-sitting-nearby-6382482/ • Shame: https://www.pexels.com/photo/ethnic-woman-frowning-face-and-pointing-at-camera-5699866/ • Together: https://www.pexels.com/photo/two-women-lying-together-on-the-floor-4556783/ • Happy Hug: https://www.pexels.com/photo/photo-of-daughter-hugs-her-mother-6190858/ • Toppling a Slaver: https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/07/europe/edward-colston-statue-bristol/index.html • Stephen Wright's image from his archives.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Nightingale Initiative for Global Health • 2020 ©